When we visited the Great Barrier Reef earlier this year for a snorkelling trip, I learnt a lot about its resilience to climate change and many other interesting facts from our Master Reef Guide. As an expert on the GBR, she corrected many misconceptions I had and shared insightful knowledge that completely changed my understanding of the reef. In this article I’m sharing some details of our trip and facts I learnt that may surprise you too.

Taking one last big breath, I let go of the ladder and lobbed myself inelegantly into the ocean as if doing an accidental salmon dive. Ahhh! I shrieked, totally unprepared for the tropical winter water to instantly enter every crevice of my wetsuit.

The season’s trade winds were in full swing, creating small waves and breaks along the reef’s periphery. I quickly shoved the snorkelling mouthpiece in to avoid gulping a second round of seawater as I waited for the Sailor to join me, smiling with excitement yet a little anxious for what I was about to see.

We were at Mackay Coral Cay on the Outer Great Barrier Reef. This is almost the spot where Captain James Cook crashed into coral on The Endeavour before naming Cape Tribulation just opposite, and it’s the only place on Earth where two World Heritage Sites meet – our backdrop being the lush peaks of the Daintree Rainforest.

While I’ve visited the reef a couple of times before, both occasions were not what I’d imagined. The fish life was pretty cool, but a lot of the coral appeared broken, bleached and not very noteworthy. It was a far cry from the pictures of vibrant coral I’d seen on reef trip billboards.

Afterwards, when I started reading the waves of news headlines about “half the Great Barrier Reef being bleached to death” because of climate change, I was left stunned.

Half of the Great Barrier Reef is dead?

I can’t tell you how long I spent researching different news sources and organisations to find out if it was actually true. To be honest, I really couldn’t recall reading about it in the news. When I think back to the crazy bushfires at the beginning of the year, the world over knew immediately that Australia was under siege. I couldn’t help but wonder that the reason why the GBR didn’t receive the same attention was because it was hidden underwater where few people see.

I then came across scientific findings which explained that 2016 and 2017 were particularly destructive years for the reef. During a prolonged el niño event where sea temperatures rose to abnormally high levels, it wiped out about 30% of coral in the first year, and 20% in the second. The GBR spans 2’300kms in length, almost the size of the USA’s west coast- which means that there would have to be a ridiculous amount of dead coral.

It was hard to comprehend the scale of loss at one of Earth’s most iconic Natural Wonders, a place I live right next door to. The news made me even more eager to visit a part of the Great Barrier Reef that was still alive and thriving.

What Lies Beneath

Our first snorkel began with the option to follow our Marine Biologist who became our underwater chaperone. As a certified Master Reef Guide, she is an expert in educating tourists about the GBR and explaining scientific gobbledygook in a meaningful way. She lead a presentation on the boat on the way over about all the amazing coral and marine life we were likely to encounter. I was still feeling sceptical that it’ll all be as good as she explained but tried to remain quietly optimistic.

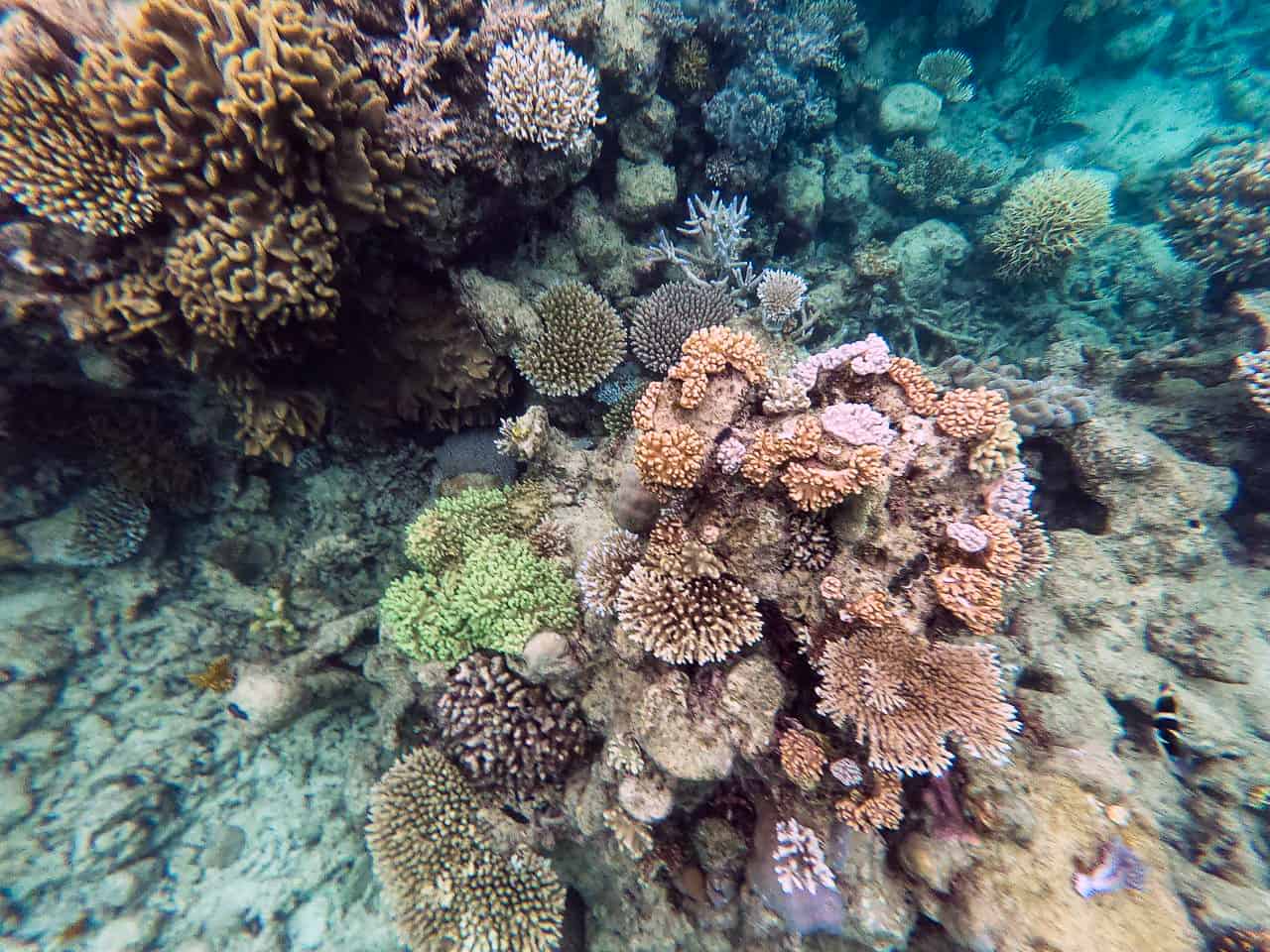

As we dunked our head in the water, after only a few strokes a huge wave of relief rushed through me. I could see a seabed full of pastel and earthy coral gardens and an abundance of different fish. The diversity was staggering.

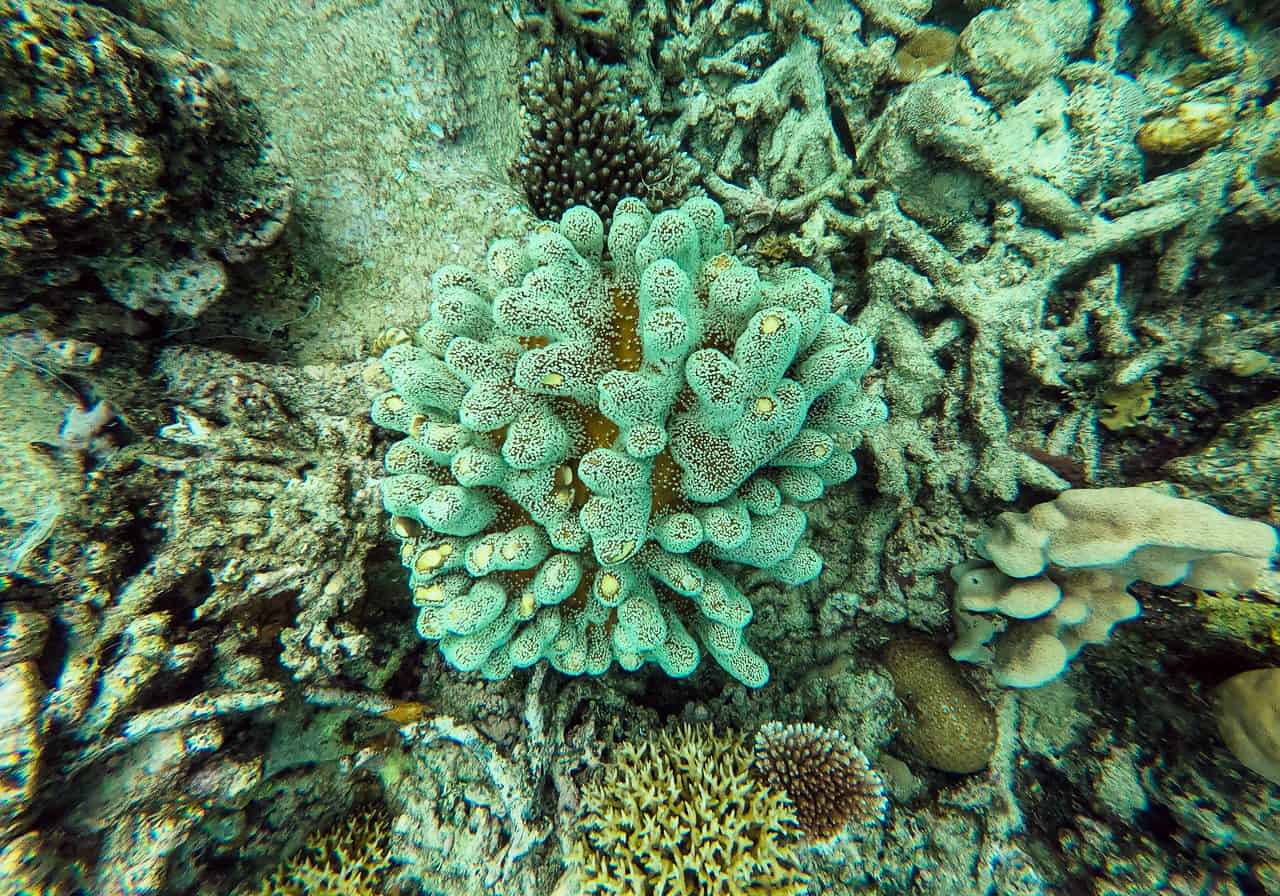

There was species of coral I’d never seen before that resembled anything from funky underwater mushrooms, to flowers, brains and fingers. The real images were far better than the ones I had in my head and my adrenaline began pumping with joy. All I can say is, phew.

We soon departed from the group to made our own discoveries and I was again covered in goosebumps when we spotted our second green turtle. There’s something truly special about seeing a turtle in the wild, they’re incredible creatures. I remembered the Marine Biologist telling us that there are only seven species of marine turtles in the world and that Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is home to six of them, how cool is that.

We followed the turtle for a while and it slowly began to steering us towards a bed of finger-shaped coral that looked less vibrant. It appeared quite slimy, like it was covered in algae and there were very few fish around. I wasn’t sure, but I presumed that this coral may have been the victim of bleaching as a result of rising sea temperatures.

On the way over the Marine Biologist mentioned that this site had seen some mortality in recent years but that over time, coral reefs have the ability to regenerate. Essentially working as a fluid ecosystem, she explained that where some corals die it leaves space for new ones to grow and take its place, like the trees in a forest.

With the amount of dead coral in this area, it seemed unlikely for that to happen anytime soon, or ever. But we saw some evidence of new growth later on when observing some smaller corals that had grown above dead ones.

It reminded me a lot of the herbs that I have growing in my back garden. Once my dill died, the parsley germinated in that pot and took over. I didn’t imagine that the same structure worked underwater too but it taught me that this is a living organism like any other, and only the most hardy survive.

In another section of the reef, I noticed that some fragments of coral were attached to the skeleton of dead coral with a metal clip.

Later on the Biologist explained that her reef operator is a member of the Coral Nurture Program, which is a long-term stewardship initiative between scientists and other reef tour companies. Their aim is to help sustain parts of the reef and improve coral cover, and one way they do this is via coral transplants.

She told us that they grow grow coral in their nurseries and then at certain times of the year they go out and plant them. So far her team have transplanted more than 1’500 coral fragments which are all growing healthily at Mackay Cay.

Whilst a reef can often regenerate over time, I learnt that more frequent bleaching events from climate change give these organisms less time to fully heal. This intervention is designed to help the reef recover and assist in its adaptation to climate change.

A Big Little Love Story

Healthy coral should be a pastel or earthy colour, however I noticed a few vibrant corals that gleamed brighter shades. I remembered our expert mentioning that certain species illuminate when they’re poorly, which really surprised me.

On previous snorkelling trips I used to search for brightly coloured coral thinking its healthy when in fact the opposite was true. It’s actually dying and putting on a ‘florescent show’ to try and attract the algae back.

She explained that algae is to coral what Romeo is to Juliet.

This symbiotic love story exists because algae lives in the tissue of the coral, making oxygen & food for it through photosynthesis – and the coral repays the algae by giving it a protected environment. Smooch smooch, kiss kiss. 👩❤️💋👨

So when the algae is no longer inside, the coral becomes sick and will eventually starve & perish if the algae doesn’t return.

She went on to mention that some coral here illuminated more than normal earlier on in the year during a long heatwave (which was actually the hottest recorded temperature on the Great Barrier Reef) but that it since recovered as sea temperatures lowered once again.

I was amazed that it could regain health so quickly and pointed out the more vibrant corals below which I thought were stressed, but apparently it was perfectly healthy. I was told that because it wasn’t a sunny day the coral appeared more colourful in the water.

Coral Bleaching – is it a death sentence?

Another small nugget of hope I was pleased to learn is that bleached coral isn’t dead, and neither is it always a death sentence. If it were then there’d probably only be about 20% of the reef left.

Bleaching happens when algae leaves the coral tissue causing it to turn white. If only mild or moderate bleaching occurs and conditions return to normal, then coral usually recovers by attracting the algae back in a matter of months.

This year saw the third mass bleaching event on the GBR in five years. Though thankfully most sites that experienced mild to moderate bleaching have already recovered or are expected to over the coming months.

In more extreme cases where up to 80% of a coral reef has been affected, mortality is typically higher. However some reefs may still recover in 9-12 years if there isn’t a second bleaching event or cyclone.

The issue right now though, in the age of climate change, is that reefs which have experienced extreme bleaching are being bleached again before they have a change to regenerate. These events used to happen every 25-30 years before global warming, but now they’re occurring around every six years. This is why curbing climate change is the main pivotal factor in ensuring its survival.

* * *

After our first snorkel, everyone climbed in the glass-bottom boat and the atmosphere was buzzing. I felt so inspired and relieved, and couldn’t wait to tell the world “hey guys, the Great Barrier Reef is still great! Come see it”. But at the same time, I also felt awashed with eco-anxiety and grief.

I was already aware that if global warming increases to two degrees, predicted by 2050, then all coral reefs around the world would die. If warming is curbed to 1.5 degrees, then 70-90% would still perish. We’re already at 1°C, and the effects on our reef so far have been fatal.

Visiting the GBR today made me fully appreciate what’s at stake and I wondered whether it will still be here a decade from now.

A friend of mine, a Port Douglas local whose been diving around the Great Barrier Reef near here for years told me that when she first saw these sites 15 years ago, she thought it was the best coral reef she’s ever seen. She’s since visited many coral reefs around the world but always claimed that the diversity of marine life and vibrancy of the coral on the GBR was just unparalleled.

Then when she returned to those same sites a few years ago, those places that bought her so much joy before just left her in tears. We both got teared up just talking about it. She said that so much of it has just gone, that it was like a graveyard.

Since our trip I’ve been following reef updates from scientists, marine biologists and passionate stewards in the news and via Social Media. They’re doing enormous and incredible work to help adapt & sustain the Great Barrier Reef during the challenges of today, and it made me remember that at the frontline, the reef is in good hands. Currently the GBR is the best managed marine park in the world, though sadly, Australia is still being governed from the top by coal lovers who care more for a dime than the reality of climate change.

Any scientist will tell you that the reef’s survival is only possible if global greenhouse gas emissions are reduced. While we may not have a world full of Jacina Ardern’s yet, climate action has come a long way in recent years and so far a number of countries have planned to be carbon neutral by 2050, just as more of us are finding ways we can reduce our individual footprint. We just need to keep our finger on the pump.

I left the Great Barrier Reef today as an ambassador. Whilst it may not be quite as dead as we think, we do need to take better care of it. I just hope we get there in time.